Download a printable PDF version…

Download a printable PDF version…

After the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent economic depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched a massive bureaucratic structure called the New Deal whose primary goal was to put America back to work. Between 1935 and 1943, the WPA or Works Progress Administration (later changed to Work Projects Administration) was established by presidential order and employed more than 8 million workers. Seven percent of the WPA budget went for arts projects, producing 475,000 artworks through the Federal Writers’ Project, the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Music Project, and the Federal Art Project—collectively called “Fed One.”

The efforts of the Federal Art Project are mainly known today by the 4,000 public murals that survive on the walls of schools, hospitals, and other public buildings. Perhaps least known, by virtue of the fragile nature of paper and cardboard, are the more than 2 million posters that were printed by the Federal Art Project’s poster division. These posters were based on 35,000 designs, of which approximately 2,000 posters survive today. Sadly, nearly 33,000 poster designs have been lost forever, representing 99.9 percent of our public poster art.

The efforts of the Federal Art Project are mainly known today by the 4,000 public murals that survive on the walls of schools, hospitals, and other public buildings. Perhaps least known, by virtue of the fragile nature of paper and cardboard, are the more than 2 million posters that were printed by the Federal Art Project’s poster division. These posters were based on 35,000 designs, of which approximately 2,000 posters survive today. Sadly, nearly 33,000 poster designs have been lost forever, representing 99.9 percent of our public poster art.

The early posters were individually hand-painted in one or two colors and were produced in very limited quantities. Poster subjects included art, theater, travel, education, health, and safety. Initially, about a third of the artists producing these posters resided in New York City; however, by 1938 the WPA/FAP poster divisions had spread to all 48 states, with the Chicago units producing as many as 1,500 posters per day—in up to eight colors—for as little as ten cents a poster. This prolific output was largely due to Anthony Velonis and his implementation of the silkscreen process.

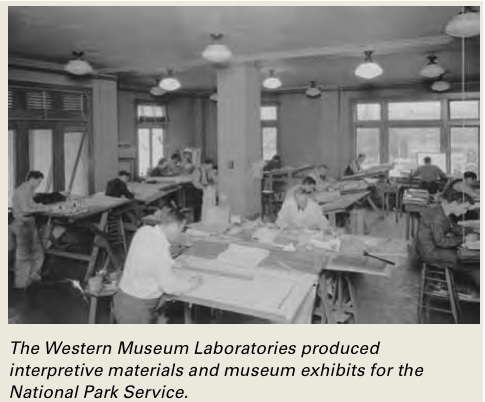

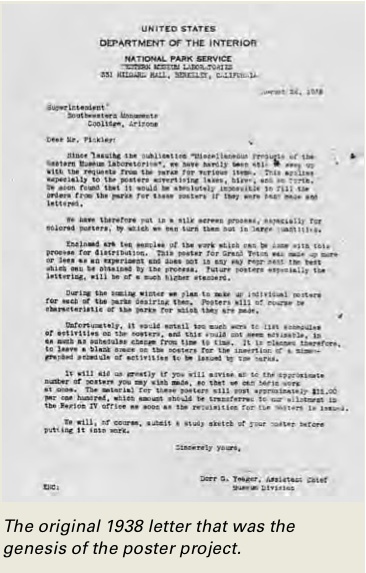

On August 26, 1938, the National Park Service poster program was launched by Dorr Yeager, assistant chief of the Museum Division of the Western Museum Laboratories in Berkeley, California, using WPA artists. In his letter to Frank Pinckley, Superintendent at Southwestern Monuments in Coolidge, Arizona, Yeager clearly adopted the improved silkscreen techniques of Anthony Velonis. Accompanying this letter were 10 poster designs, which included a preliminary sketch for Grand Teton National Park. In this letter Yeager stated:

On August 26, 1938, the National Park Service poster program was launched by Dorr Yeager, assistant chief of the Museum Division of the Western Museum Laboratories in Berkeley, California, using WPA artists. In his letter to Frank Pinckley, Superintendent at Southwestern Monuments in Coolidge, Arizona, Yeager clearly adopted the improved silkscreen techniques of Anthony Velonis. Accompanying this letter were 10 poster designs, which included a preliminary sketch for Grand Teton National Park. In this letter Yeager stated:

This poster for Grand Teton was made up more or less as an experiment and does not in any way represent the best which can be obtained by the process. Future posters, especially the lettering, will be of a much higher standard.

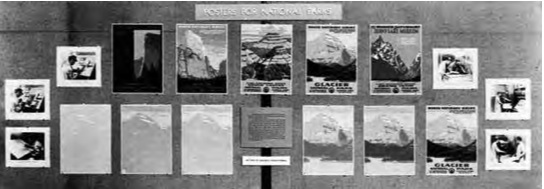

This “Jenny Lake Museum” poster stands alone in its styling and lettering, harkening to earlier stylized WPA poster designs. The Grand Teton design was taken from a recently completed diorama built under the direction of that park’s first seasonal park ranger–Fritiof Fryxell. Grand Canyon, an eight color print, and the most complex design of the 14 made, was the second of this set and bears very little lettering at all. The third in this series was Wind Cave……….From Yellowstone Geyser (believed to be the third publication) onward, most posters featured the “Ranger Naturalist Service” banner at the top with more literal graphic interpretations of National Park scenes.

This “Jenny Lake Museum” poster stands alone in its styling and lettering, harkening to earlier stylized WPA poster designs. The Grand Teton design was taken from a recently completed diorama built under the direction of that park’s first seasonal park ranger–Fritiof Fryxell. Grand Canyon, an eight color print, and the most complex design of the 14 made, was the second of this set and bears very little lettering at all. The third in this series was Wind Cave……….From Yellowstone Geyser (believed to be the third publication) onward, most posters featured the “Ranger Naturalist Service” banner at the top with more literal graphic interpretations of National Park scenes.

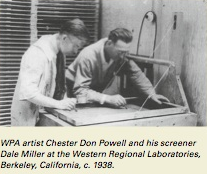

WPA artist Chester Don Powell is believed to be the chief designer of these National Park posters with the likely exceptions of the first (Grand Teton) and the last (Bandelier). Powell and screen printer Dale Miller (pictured above) managed only 14 park designs before the project was closed down by the onset of WWII in 1941. The number of posters printed of each design is unknown, but the fragility of silkscreens used at this time would have limited each edition to between 50 and 100 posters. Posters cost $12 per hundred or just twelve cents each and were distributed to local Chambers of Commerce in communities surrounding each park to encourage visitation.

WPA artist Chester Don Powell is believed to be the chief designer of these National Park posters with the likely exceptions of the first (Grand Teton) and the last (Bandelier). Powell and screen printer Dale Miller (pictured above) managed only 14 park designs before the project was closed down by the onset of WWII in 1941. The number of posters printed of each design is unknown, but the fragility of silkscreens used at this time would have limited each edition to between 50 and 100 posters. Posters cost $12 per hundred or just twelve cents each and were distributed to local Chambers of Commerce in communities surrounding each park to encourage visitation.

For 35 years, they disappeared into history. Then, in 1971, a Grand Teton poster turned up destined for the park burn-pile. It was this poster that piqued the curiosity of seasonal park ranger Doug Leen, and a 20-year effort led him to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, where 13 black-and-white negatives survived in the file drawers of the National Park Service archives. These negatives and the single poster, then the only one known to survive, were the templates used for reconstruction of this set.

As republication progressed, originals slowly began to resurface. First, two Mount Rainier posters turned up in a garage near Seattle, rescued in a similar fashion from under a park log cabin years earlier. A year later, a third Rainier turned up in an original frame, and when taken apart to clean the glass it was discovered that three posters were “sandwiched” together—the center one in pristine condition. These original colors were used for a limited edition for Mount Rainier’s Centennial, celebrated in 1999, and the other two were donated back to the National Park Service.

As republication progressed, originals slowly began to resurface. First, two Mount Rainier posters turned up in a garage near Seattle, rescued in a similar fashion from under a park log cabin years earlier. A year later, a third Rainier turned up in an original frame, and when taken apart to clean the glass it was discovered that three posters were “sandwiched” together—the center one in pristine condition. These original colors were used for a limited edition for Mount Rainier’s Centennial, celebrated in 1999, and the other two were donated back to the National Park Service.

It was then that National Parks started searching their flat-file archives for these posters, yielding finds for Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest. In 2003, researchers at Bandelier National Monument discovered 13 posters in a file drawer—some cut up and used as cardboard file dividers! In 2004, a Los Angeles art collector stumbled upon the largest single find: nine original park posters in a second-hand shop, which later sold at auction in New York City, the Grand Canyon poster bringing $9,000—the first test of value in a free market. Later, a third Grand Teton poster resurfaced as cardboard, cut to fit, in a plant press in White Sands, New Mexico. In 2012, a California attic yielded six more. Today, 41 originals have been found, with only one copy each for Yosemite, Yellowstone Falls, and Petrified Forest. The two posters

that remain unaccounted for are Wind Cave and Great Smoky Mountains. With these recent discoveries, some, but not all, of the historic posters have been corrected to accurate colors and dimensions.

Because only 14 parks subscribed to the Western Museum Laboratory’s 1938 offer to produce posters, many parks today have commissioned contemporary poster designs “in the style of the WPA.” These designs are a collaborative effort by both Doug Leen and Brian Maebius and now number over 40 parks and monuments with more planned.